|

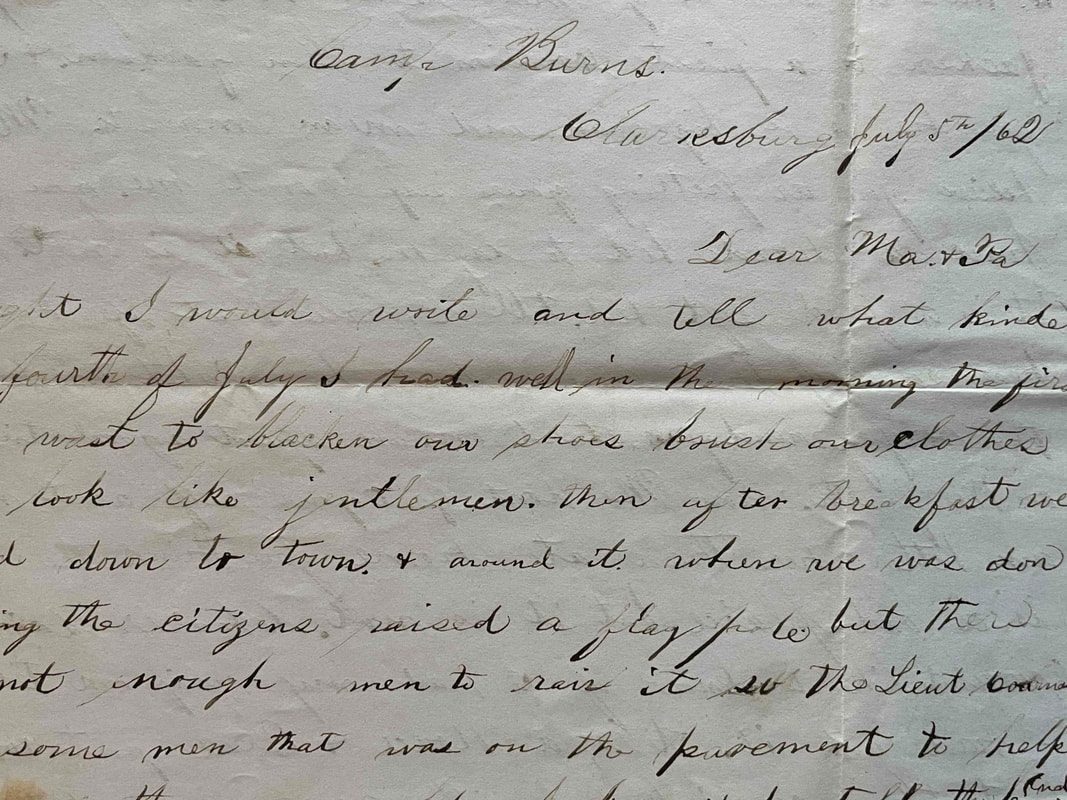

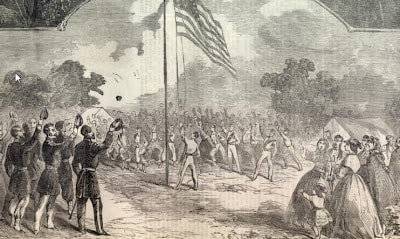

Camp Burns Clarksburg July 5th/62 Dear Ma & Pa thought I would write and tell what kinde of a fourth of July I had. well in the morning the first thing wast to blacken our shoes brush our clothes up & look like jintlemen (gentlemen). then after breakfast we marched down to town & around it when we was done marching the citizens raised a flag pole but there was not enough men to raise it so the Lieut Col. tolde some men that was on the pavement to help & monge (among) them was olde Jackson & he tolde the Cournal (Colonel) he would see him in hell first before he would help to raise a union pole. The Cournal pitched at him with his _ _ _ but olde Jackson run but we sent squads after him & that double quick too. well they caught him put him in a room but he got out then the whole Regt loaded there guns and started after him. but they soon cought him & now we have got him in the guard house. oh but we made fun of him. there was a picknic here & the Slaves(?) had one to them selves to. there are squads of men sent out every day. this Jackson is a first cousin to Lieut. Jackson (Gen. Stonewall Jackson?) & I tell you he is a big man and mean man too. Ma I believe you are fretting your self about me. you say I have a harde bed to lay on. but it is not harde it is a good soft bed. tell Charlie that if he would hear some of these canon here he might talk. it shake the very ground you stand on. we spent a good time here on the fourth. now Ma dont fret your self about me I am better here than at home. you think the Army is a bad place but it is not. Charlie said he would like to know if I had my uniform tell him I have got it. it is a Puce(?) & Blue pants. when I get tyard (tired) or sick I will come home but I dont think that will be untill the three months are up. & so you got a letter from Jim. I would like to know if he is well. I want you to tell me if you got the Captains picture now don't forget to tell me in your next letter. Dave Roach came home before I left. I think Charlie acts like a (brother or bother?) I tolde him to write & tell me about all the boys. tell Willie Zimmerman that we make the rebbels run when we get after them. please write often and I will to. I have just been in swimming & I was washing some clothes. I want you to tell me all about the fourth of July in Minerva. tell that Joe Milner dont write I will never write to him again. just tell him so too. ask him if he is going to stick to his promise. I would like to see you all but we are a great ways a part & it is in vain to see one an other. I would like to help Pa if I could. By the way you talk Pa must be taking the wool in. tell Charlie (Frank's younger brother) he must do all he can for his Pa & be a good Boy. tell Birt Kitzmiller to write tell him that perhaps we will go to where is the man that Baked pies for the 32nd Regt he Bakes for us & he said he knowed John Kitzmiller, & all the Boys in Potts Company. I would give five dollars if the whole family was here to pick black berries I will bet you neve (never) saw as menne (many) in your life the hills as just covered with them I know of one patch which is 20 Achors (acres) wide & 50 long. you said you was at Sandyville when you write tell how they are all getting. be shure not to forget to tell me about that picture of the Capt. tell Will Haldeman to answer my letter that I wrote to him. tell Simon that I can back(?) him out enna day he ever saw. oh yes I am going to keep my other clothes here because I mite get wet & then I would have something dry to put on. I had some Mulberries as long as my finger. now I want you to write as long a letter as this and a little longer so please write soon. my love to all of you & to Johns folks. & to Uncle Bills & Jeromes to. kiss the little ones at home that is Johns & Bills & Jeromes. from your son Frank I have more questions than answers about this fascinating firsthand glimpse into the controversy surrounding the celebration of our country's Independence Day during the Civil War. It is just one example of the various ways it was observed at such a fractious time that called into question the very legitimacy of our United States. Whether northern, southern, white or black -the holiday celebrating freedom and independence took on many meanings that changed over the course of the Civil War as it dragged on. The skirmish that took place around raising the Union flag in a town where loyalties were divided, was likely typical. And it shines a light on how personal the war was... the enemy was your neighbor or even a relative, not a stranger from another country. Having read that Clarksburg was the home of Stonewall Jackson, I am taking a guess that the guy they put in the guard house may have been his relative. Also, it is very interesting that Frank notes the "Slaves" had a separate picnic that day. This must refer to the slaves living in the town, celebrating the hope that a Union victory might one day secure their freedom. The letter also gives us more insights into Frank's day-to-day life at the camp. Between picnics, pies, blackberries and mulberries, it is pretty clear that in this and all of his letters, food was definitely central to his days. He mentions a "good soft bed" and seems very proud of his uniform.... and he talks about swimming and washing some clothes (probably to please his mother). He mentions several times about sending them a picture of the Captain (Andrew V.P. Day) and did they receive it? Not sure why that would've been so important... I could not find any other information about Capt. Day. It seems like his family would rather have had a picture of him! But perhaps the one portrait was all a drummer boy was entitled to. At the same time, Frank takes this opportunity to mention a number of friends, family members and places near home in Minerva. He talks about a Joe Milner - "I will never write to him again... ask him if he is going to stick to his promise" -- no idea what that is about! But some of the names I do recognize from my family records: I believe Uncle Bill and Uncle Jerome would have been brothers of his mother Mary Ann who was a Zimmerman, which leads me to guess that Willie Zimmerman must have been a cousin (probably son of Uncle Bill). Uncle John may have been a brother of his father (Henry A. Foster). He mentions he "would like to help Pa with taking the wool in." My records show Henry owned a Dry Goods store, but the family must have also had a small farm to manage. Frank also mentions Sandyville, which is about 20 miles west of Minerva. Sandyville is where his mother's family was from. (More about Franks' parents - the Zimmerman and Foster histories in future posts). Just an aside: Birt (Bert?) and John Kitzmiller must have been friends of the family. Frank talks about a pie baker for his regiment as well as the 32nd Regiment who "knows John Kitzmiller and all the boys in Potts Company." The 32nd Regiment was organized at Mansfield, Ohio (about 80 miles west of Minerva). The commander was Col. Benjamin Franklin Potts who was later promoted to brigadier general in 1865.

0 Comments

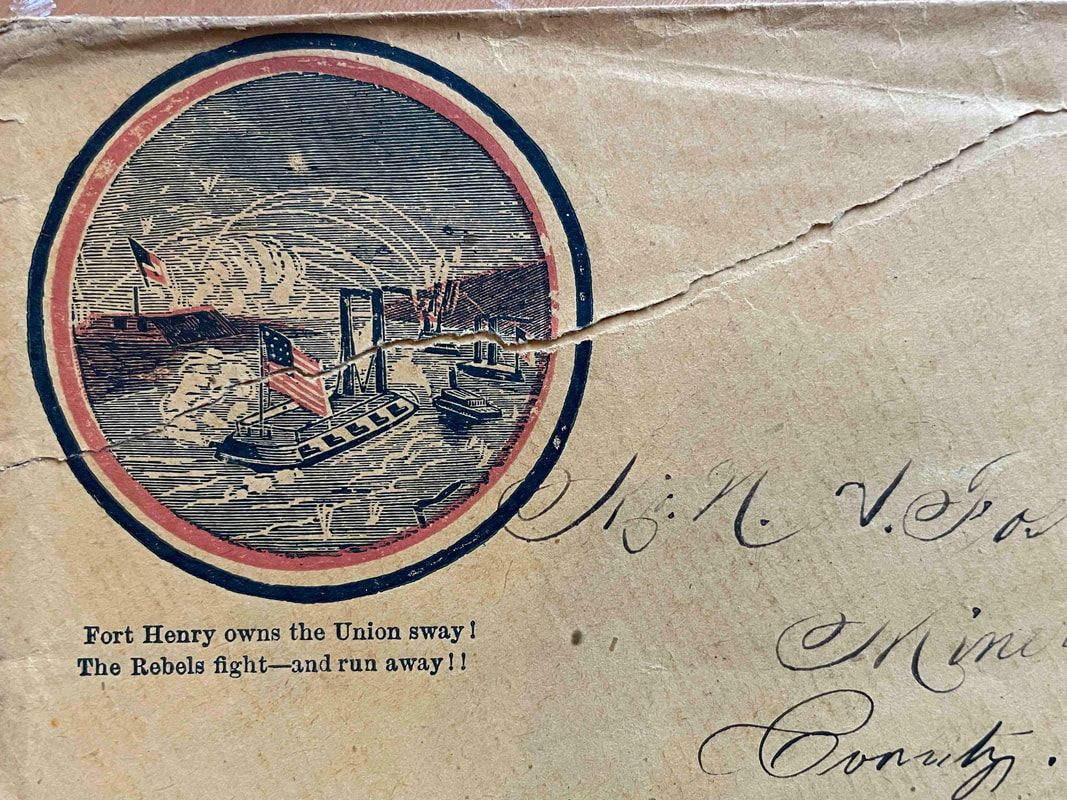

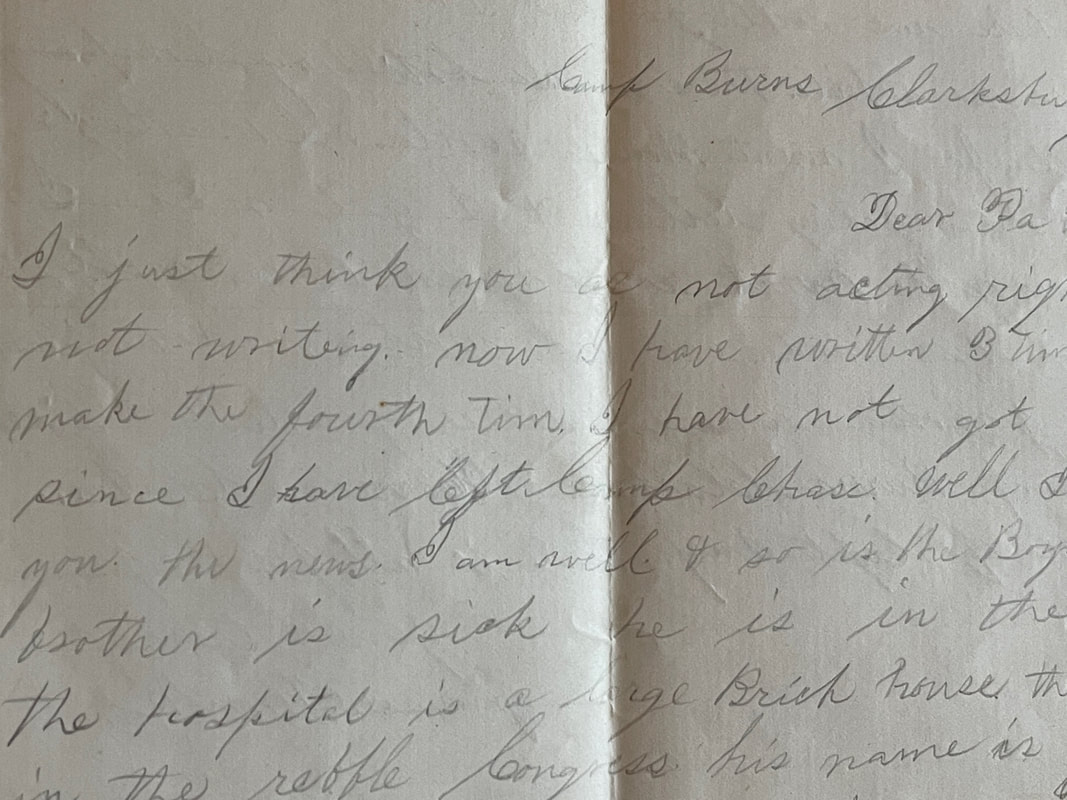

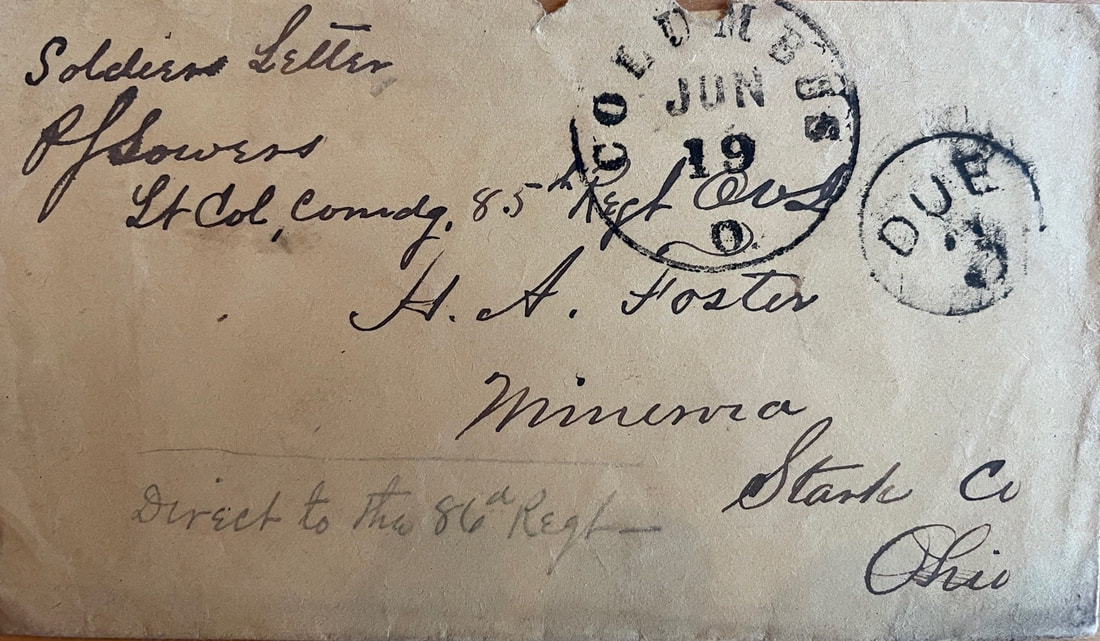

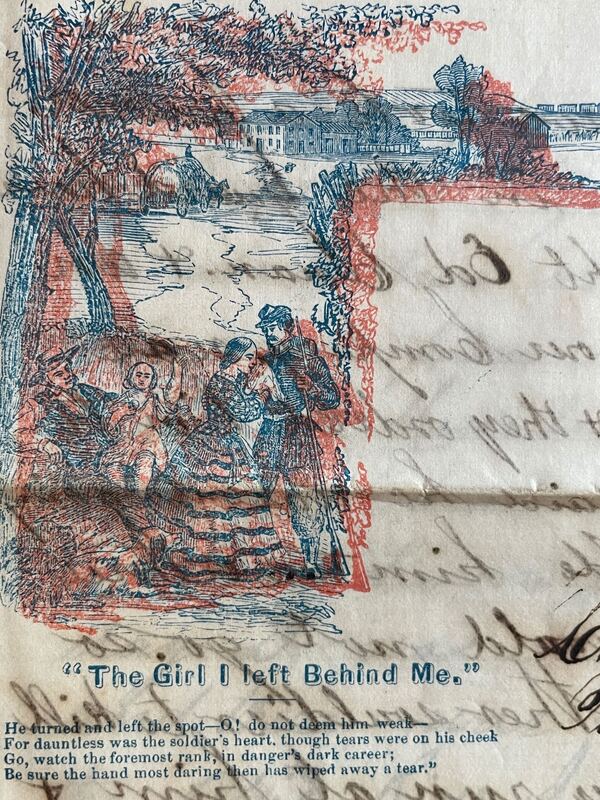

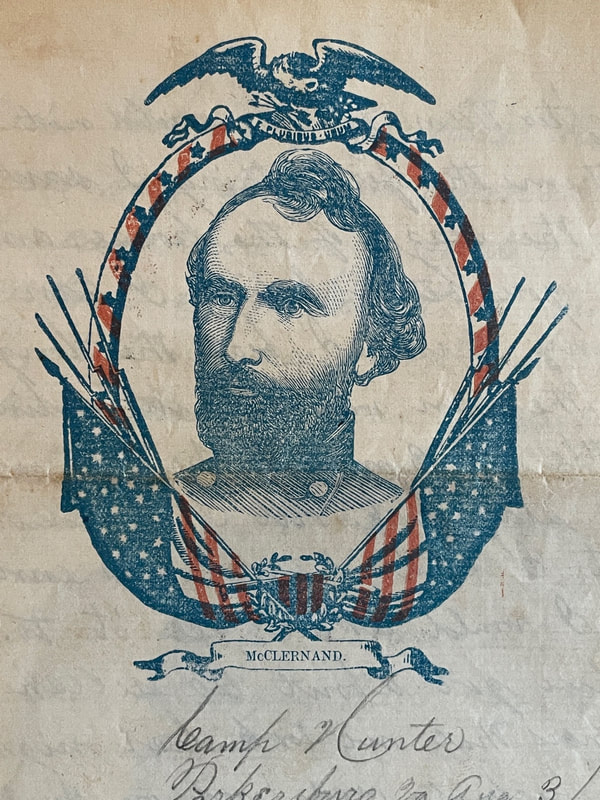

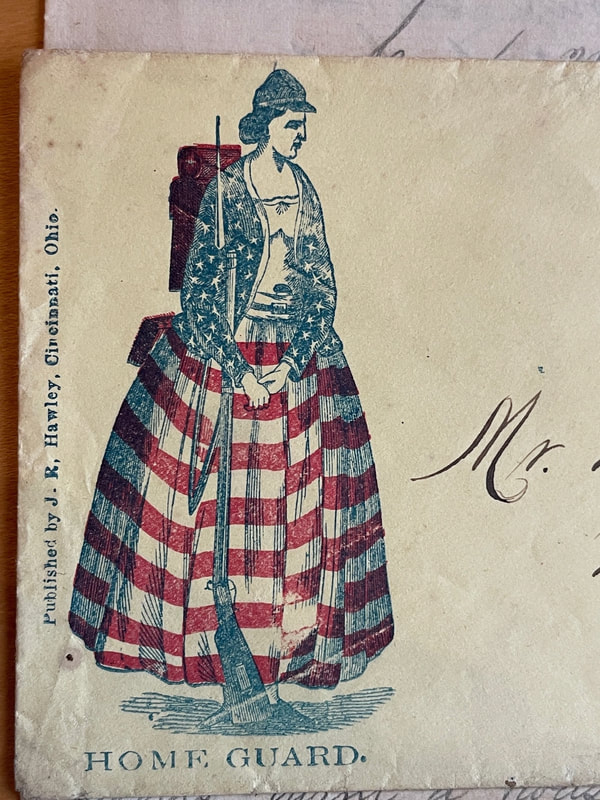

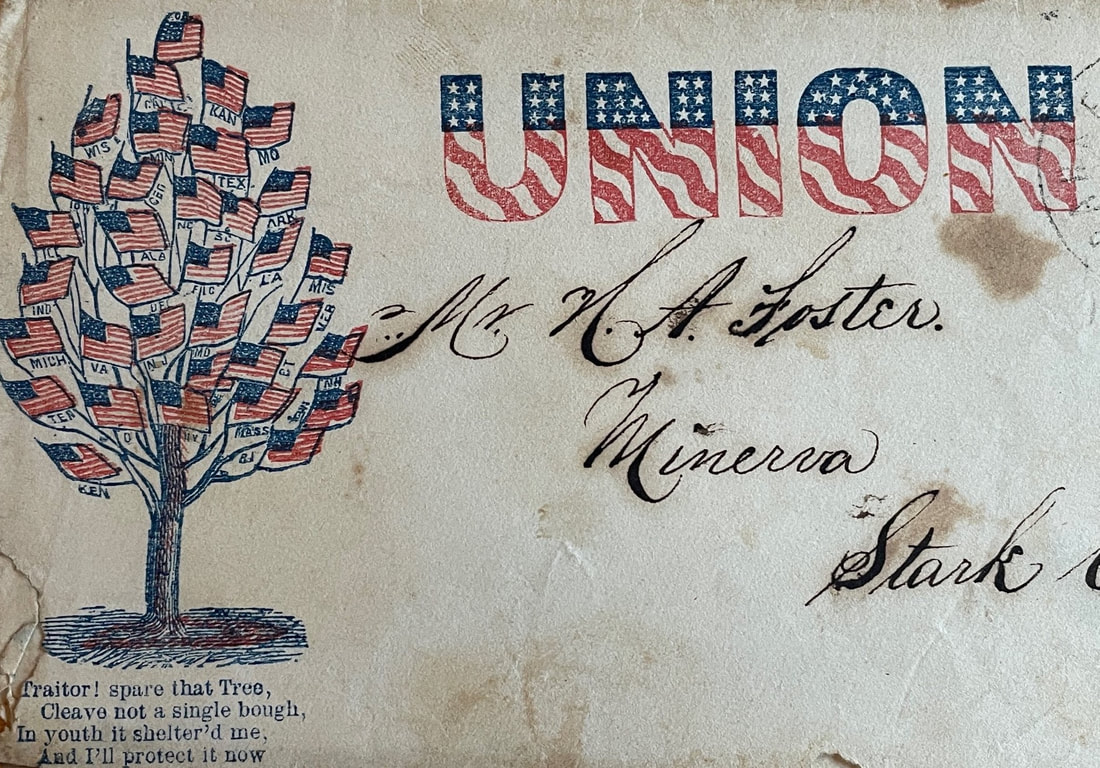

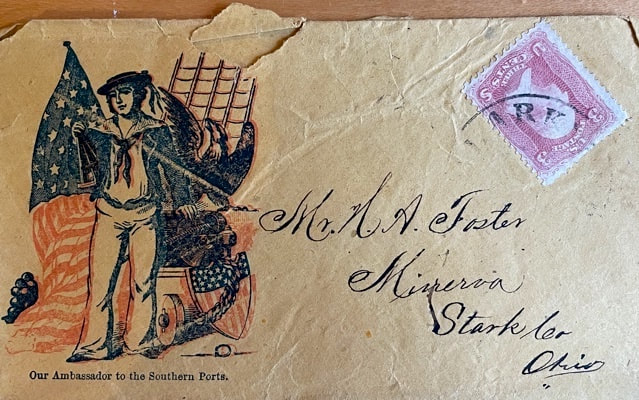

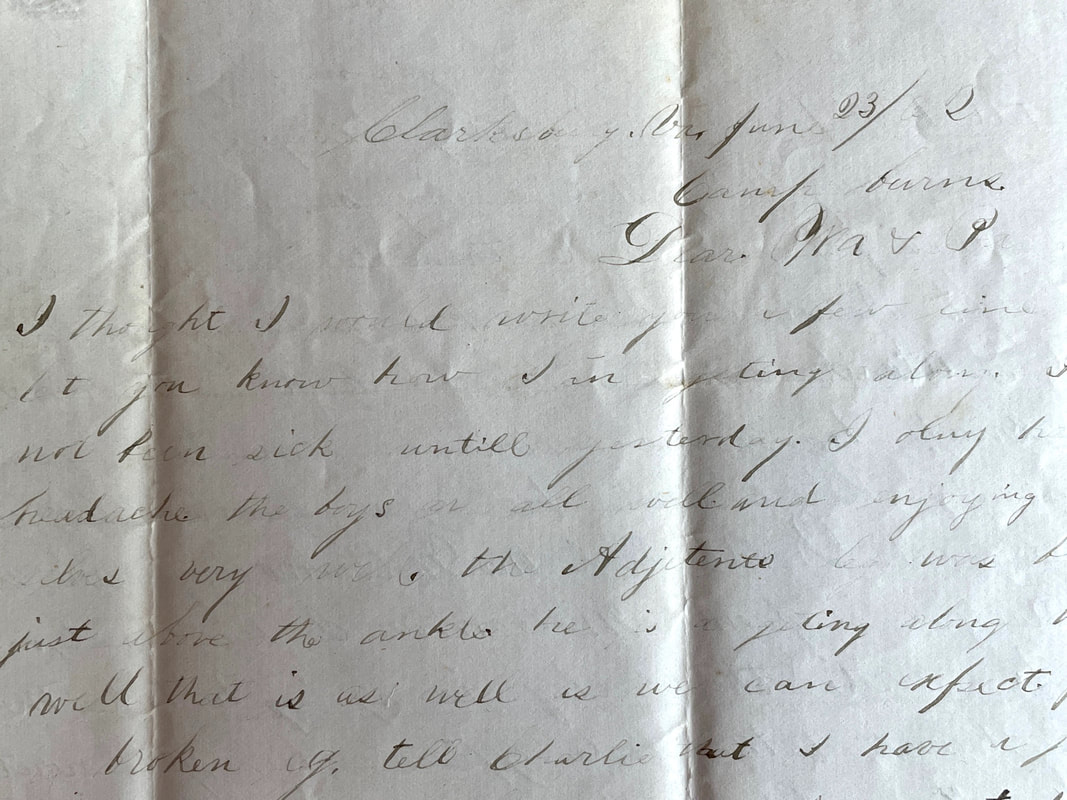

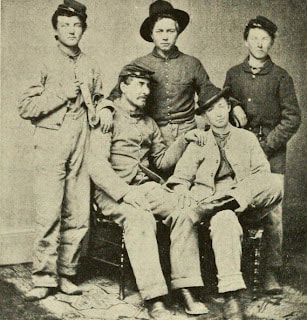

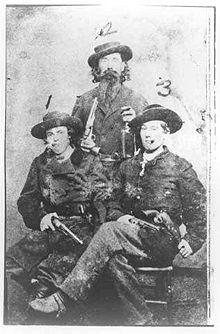

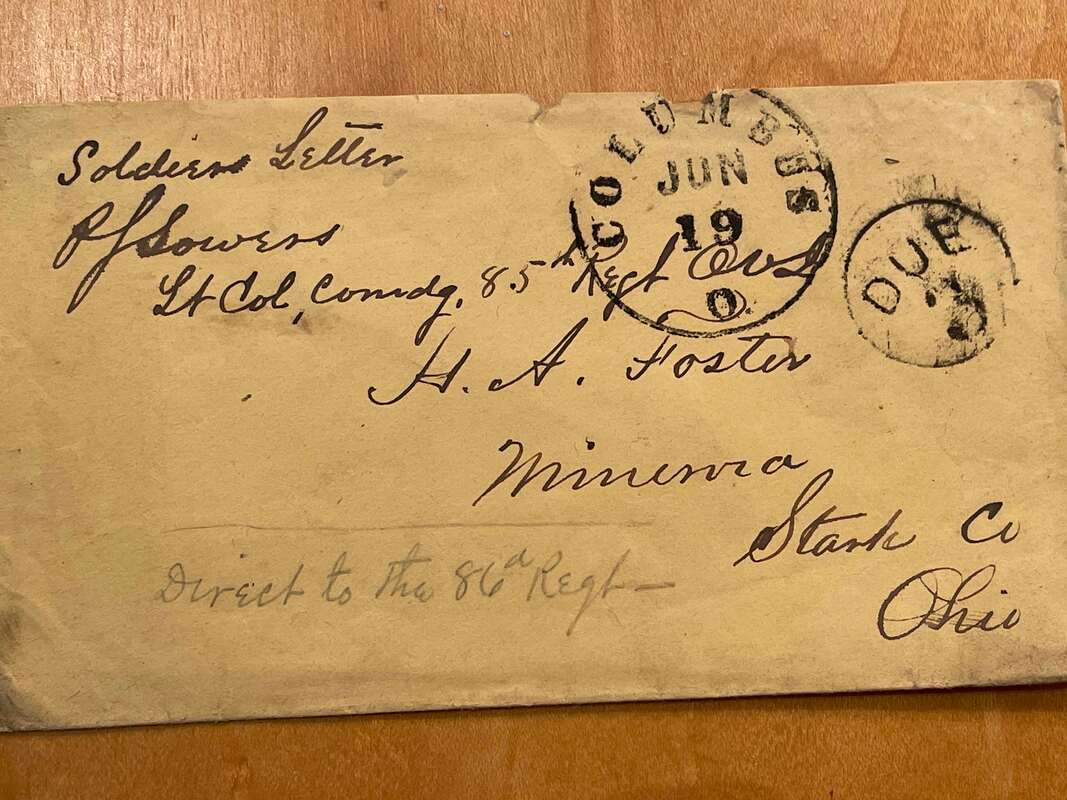

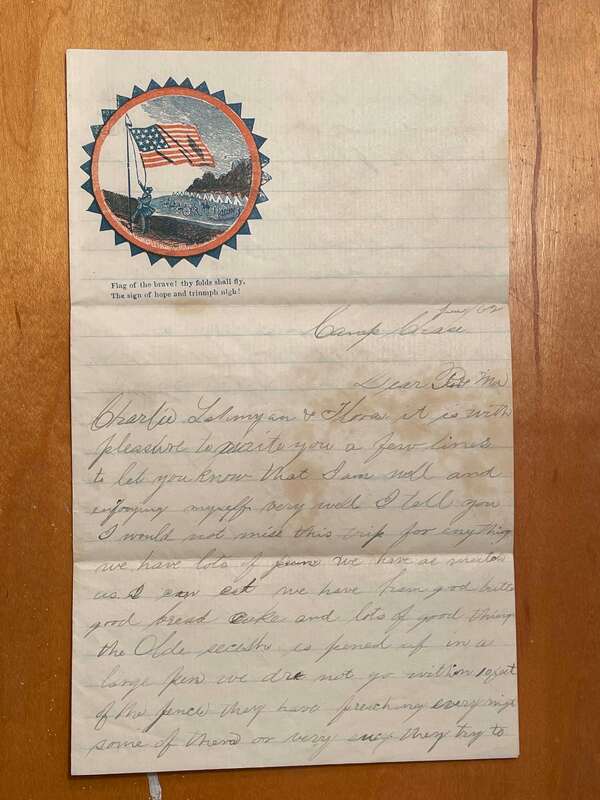

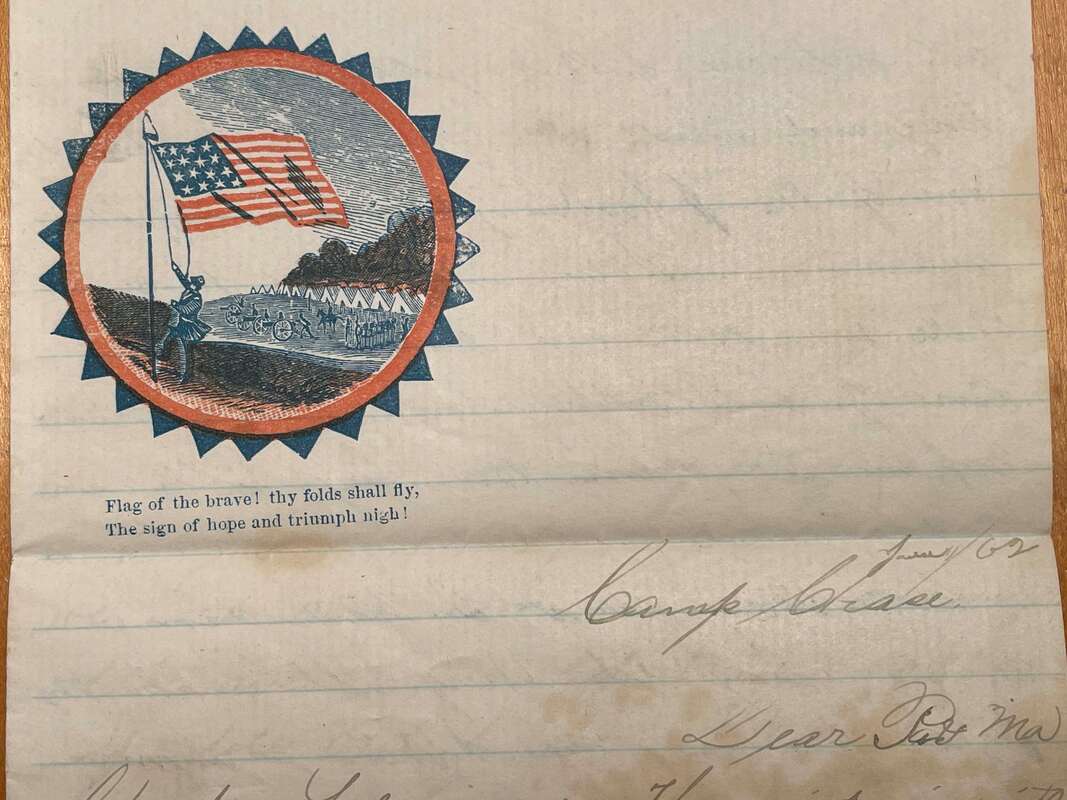

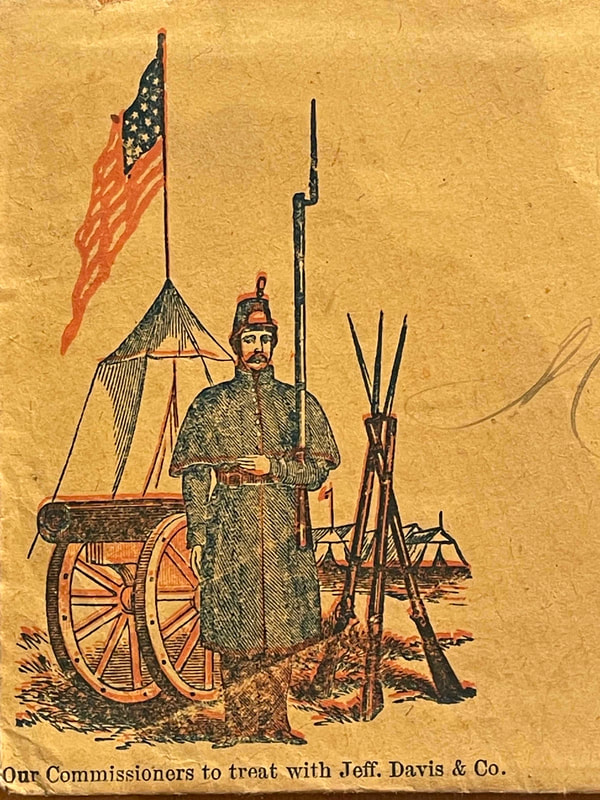

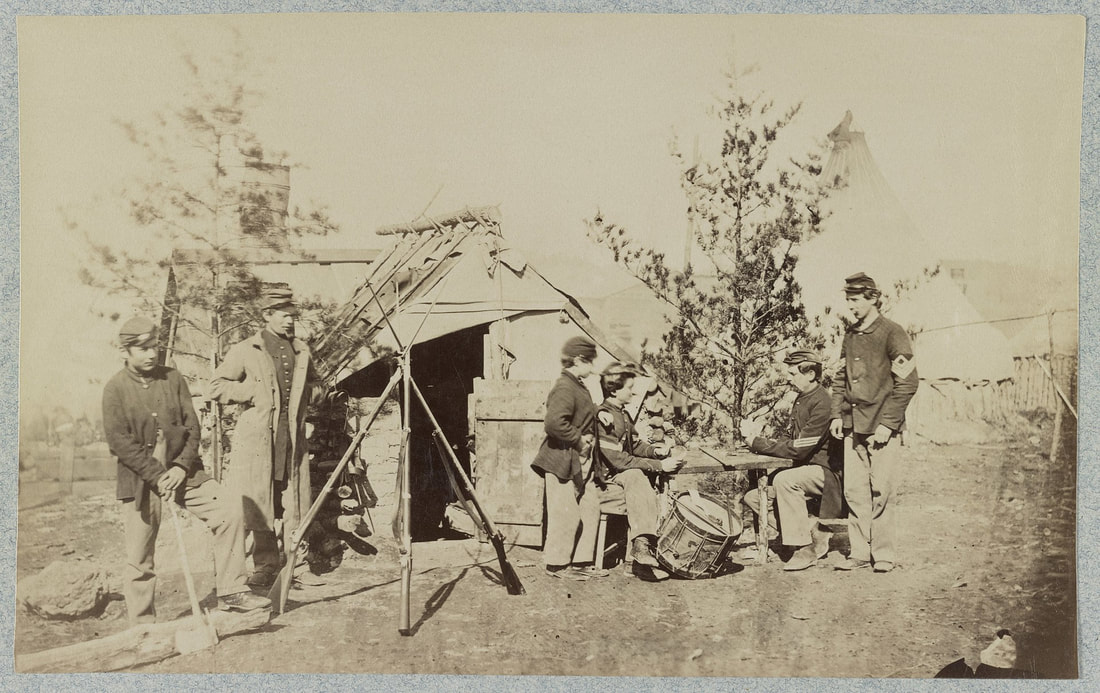

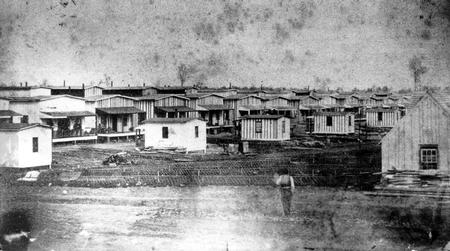

As Frank's second letter from Camp Burns in Clarksburg, Virginia (later West Virginia) opens, he mentions that the Captain's brother is in the hospital: "a large brick house, the man (owner) is in the rebel Congress.... it is as nice a house as I or any other person should live in." During the Civil War it was very common for occupying forces of either side to commandeer local homes for hospitals and other military uses. I was not able to discover any more about the owner Johnson, but did learn that Clarksburg was firmly controlled by the Union for the entire war (despite being the hometown of Stonewall Jackson!) As a result, Frank was relatively safe at Clarksburg -- the only real threat being illness. In this letter he seems to be in good health and eating well: "There are lots of ripe fruit here.... I am growing and getting... fat." Again, like taking over private homes, the soldiers were stealing freely from the orchards and crops of the local Confederate farmers who were off at war. Frank goes on to say: "We do not know where we will go, but I think we will stay here for a while. There is an artillery company here." Reading a little bit more about Clarksburg's role in the war, Frank's impressions make sense. According to Clio, a non-profit educational website: "Clarksburg was the site of no major battles or skirmishes. However, it was a crucial supply depot for Union supplies. General George B. McClellan established his headquarters near the city during the early phases of the war. At one point, Clarksburg had seven thousand soldiers camped in the city, prepared to defend supply lines from Confederate attacks. Despite the Union presence in the city, Clarksburg was a town divided. Throughout the war, personal loyalties of Clarksburg citizens remained divided, though Union control of the area was firmly maintained." Camp Burns Clarksburg June 29/62 Dear Pa & Ma I just think you are not acting right for not writing. now I have written 3 times & this make the fourth time. I have not got one letter since I have left Camp Chase. well I will tell you the news. I am well & so is the Boys. the Capt's brother is sick he is in the hospital. the hospital is a large Brick house the man is in the rebble Congress. his name is Johnson. it is as nice a house as I or enny other person should live in. Addam Bowers is not well. did you get that letter that have the Capt's picture. I want you to tell me if you did tell Flora not to spend that 10 dolar bill. the (lears or cars?) runs here on sunday. I have to drum on sunday for bitallain drill. there are lots of ripe fruit here. I had some cherries. some of the corn is as tall as I am. the Boys say that I am growing & getting as fat they said they neve saw enny person pick up as fast as I do. we do not know whare we will go But I think we will stay here a while. there is a Artillery Company here. tell Jo I want him to write. all the Boys in the Co is getting letters & I get none. I think you mite write every week once. well it is getting late and can not write mutch. perhaps you have forgotten where to direct your letters direct them to Camp Burns Clarksburg. Harrison Co. Va. in care of Capt Day. that is all for the preasant. yours truly your son, Frank Some of the most prolific cries in Civil War soldier's letters is "Why don't you write me more?" and "Tell everyone to write me!" Mail delivery was highly anticipated by soldiers who felt left out of the events on the home front. Letters were a huge source of information and the main source of communication back home to the common soldier. It was reported that some regiments were sending out around 600 letters per day. Stationery and envelopes during the Civil War period were beautiful. They typically featured patriotic messages, imagery and political cartoons. It was not uncommon for envelopes to be as decorative as the stationary. Soldiers had the option to write "Soldier's Letter" on the front of their envelope to have the recipient pay for the postage due to the trouble of tracking down stamps and keeping stamps usable in the field. Above quoted from "World Turn'd Upside Down" blog post by Stefanie Ann Farra and also above, see an example of a Soldier's Letter sent by Frank when he had first arrived at Camp Chase. Here's a little bit more about Civil War stationery quoted from an article by Veronique Greenwood published in National Geographic 12/10/2015.... In 1861 and the years that followed, many American men found themselves far from home... More than 2.6 million men joined the Union Army over the course of the war, while roughly a million joined the Confederate forces. The volume of mail ticked upward with letters to distant homes, and when it was time to send a letter, soldiers and civilians alike reached for a new kind of envelope, freshly printed and decorated with red and blue flags, delicate engravings of eagles, poems about the girl left behind, or the faces of generals, whom people at home might never have seen. There were many such envelopes to choose from: Over the course of the war, 10,000 or more Union designs were printed, says Steven Boyd, a historian at University of Texas, San Antonio. “You could buy a hundred different designs in a single packet for one dollar,” he says. This riot of creativity was sparked by, of all things, a change in postal rates. When we drop a letter in the mail now, we don't think of the envelope as a luxury. But until the mid-19th century, U.S. postage was charged by the sheet, so people simply folded their letter and used sealing wax to close it. Reforms to make letters cheaper, however, meant that by 1851, there was a flat 3-cent rate for mail under a half-ounce and traveling less than 3,000 miles. Envelopes, made on newly invented envelope-folding machines, flew out of stationery stores. Two more examples of Civil War stationery....... Camp Burns Clarksburg, Va June 23, 1862 Dear Ma & Pa I thought I would write you a fair line to let you know how I am getting along. I have not been sick untill yesterday. I _____ headache. The boys are all well and enjoying themselves very much. The Adjetent's (Adjutant - a staff officer) leg was broken just above the ankles he is a getting along very well, that is as well as we can expect from a broken leg. Tell Charlie that I have a good drum. There was a battery came here yesterday and they left for Buchanan (about 200 miles to the southeast; the front line of the Union campaign). They were all good men and big ones too. They had the best lot of horses I ever seen. There are not many seccesh (Secessionists - Confederate soldiers) about but there are a few bushwackers (informal Confederate militia). But they are very scared. I like the army very well. The boys will give me anything they have if they something that I have not got they will always share. Tell Charlie I am not afraid to drum with enna thing about Minerva and tell him that I want him to answer that letter and tell me all about the boys in Minerva and how they are getting along. When you write tell how John is a getting along. I want you to tell me everything that is going on. If there is enna letters comes for me sends them to me. We have a good Capt. John Maron makes a very good First Leutenit. But the second Leut is not worth one snap. He runs about to mutch his name is Blackford. He is from Molborrow (Marlboro, OH about 18 miles north of Minerva). Tell Suckie Woode that the Molborrow boys are well. This Blackford is from Molborrow. I have not mutch time to write the Ordley is a going to take the letters downt to the poste office when you write tell how Fave(?) Shane is getting. George Davis is a good boy. He tendes to his business very well. I believe that is all at presant. Yours truly, Frank P.S. When you direct you letters direct them this way Clarksburg Camp Burns. Harrison Co, VA At the time this letter was written, Union forces in the Midwest, including the Ohio 86th Infantry were tasked with attempting to take control of what is now considered West Virginia, and advance the Union line towards today's Virginia/West Virginia border near the town of Buchanan that Frank mentions. Ultimately the Union was only able to control as far as Raleigh, WV, about 120 miles to the west. Up to this point, I have not been able to identify the various officers, soldiers and friends Frank refers to in his letters; but I continue to keep my eye out for clues in other correspondence and photos. One thing is for sure - he is very proud of being a drummer boy! The above photo was found on the website of an independent researcher, Dennis Segelquist, who discovered it in a firsthand account: "The History of the 86th Regiment Ohio Volunteer Infantry" written by Private Joseph N. Ashburn. The young soldiers pictured were between the ages of 18 and 25 and were identified as Privates; except for the boy at front right who was 17 and a Musician -- about as close as I could get to a photo of Frank's actual 86th Regiment, Company I. Confederate Bushwackers or non-enlisted militia, were prevalent in the West Virginia area where the Ohio Infantries were deployed in the years 1862-63. According to Civil War historian, Kenneth Noe, these guerilla fighters were not necessarily "young and landless outlaws on the fringes of society," but as often as not they were "older and propertied men and their sons;" at least during these early years of the war, which often consisted of spontaneous conflicts to maintain local control of the land, rather than battles fought in a wider military strategy. Below is a photo of some 1860's Bushwackers. When reading Frank's letters, it helps to keep in mind the itinerary of Company I's activities over his three-month enlistment period. Below is a brief summary, courtesy of the Ohio Civil War Central research website. They note that During the 86th Regiment Ohio Volunteer Infantry’s term of service, thirty-eight men, including one officer, perished from disease or accidents. No men died from wounds received on the battlefield. June 11, 1862 The 86th Regiment Ohio Volunteer Infantry mustered into service at Camp Chase, at Columbus, Ohio. The men in the regiment were to serve three months. June 16, 1862 Officials dispatched the 86th to Clarksburg, Virginia (modern-day West Virginia). Upon arriving at Clarksburg on June 17, the regiment primarily served on garrison duty at Clarksburg and Grafton and on guard duty along the railroad. July 27, 1862 Authorities ordered Companies A, C, H, and I of the 86th to Parkersburg, Virginia (modern-day West Virginia) to help fend off an anticipated Confederate attack. The assault did not materialize, but these companies remained at Parkersburg except for Company H, which guarded railroad track located east of the city. August 21, 1862 The regiment consolidated at Clarksburg before moving to Beverly, Virginia (modern-day West Virginia) to prevent a Confederate invasion of western Virginia and Ohio. The Confederate force advanced in a different direction before reaching Beverly, and the 86th returned to Clarksburg, where it performed garrison duty for the remainder of its term of service. September 17, 1862 The 86th Regiment left Clarksburg for Camp Delaware at Delaware, Ohio. The regiment arrived at Camp Delaware on September 18, 1862 and mustered out of service on September 23, 1862. Now we begin with Frank's first letter written from Camp Chase on June 12. Camp Chase June 12/62

Dear Pa & Ma, Charlie, Lollmy (maybe a nickname for Marion) & Flora it is with pleasure to write you a few lines to let you know that I am well and enjoying myself very well. I tell you I would not miss this trip for enything. we have lots of fun we have as mutch as I can eat we have farm(?) good butter good bread cuke and lots of good things. the Olde secesh is pened up in a large pen. we do not go within 10 feet of the fence. they have preaching every night. some of them ar very ency (antsy?) they try to get out. one of them got en olde case knife (table knife) - and made a saw and he sawed one of the bordes off. then one of the guards saw him and shot him. there wer 1000 men drawn up in the line of battle. they looked very nice. when i came the boys all ran and wanted to know if I came when they new I had came(?). they was glad. they all make the bigest fus over us. their is a man coming with some straw berrys. I must stop and get some. Well I have ate my berrys now there is as many wagons here as there ar in Minerva. and of all the fun I cannot tell. I can not mutch it is to mutch nois so you must excus my mistakes. I mess (eat) with the Captin Liet Brandt. we have a little coock I tell you now he can coock. he can fry the ham just right. we will get our uniforms today or to morrow. I have got my Drum. I must hurry there is more that was(?) write so I can not write mutch. the captin is in town. I mean Columbus when I say town. his brother is sick and he is taking care of him. the corn is very high here. the Boys just make a fuss(?) of me. they will give me everything. we live in as good a shanty as there is in camp. we lock our door every now. one night while we was assleep they came in and stole our bench. I have no more to write now. they are a going to drill now sow good by Yours truly F.A. Foster This first of eighteen letters to Frank's mother and father, is actually not from Frank, but from First Lieutenant, Charles C. Brandt, who was among the officers in charge. According to records found in the on-line Minnesota Legislative Reference Library, he was born in 1837 making him 25 years old when he wrote this letter. It says he moved to Minnesota from Ohio around 1864. He was a farmer/mechanic by trade, and in 1877 was elected to serve in the Minnesota House of Representatives. Below is the transcription of First Lieutenant Charles C. Brandt's letter. In all transcriptions, the faded handwriting has been deciphered to the best of my ability. However, there are gaps in places that were illegible to me. For the most part, the words of the letter have been transcribed with original spelling and grammar. Camp Chase June 10th 1862

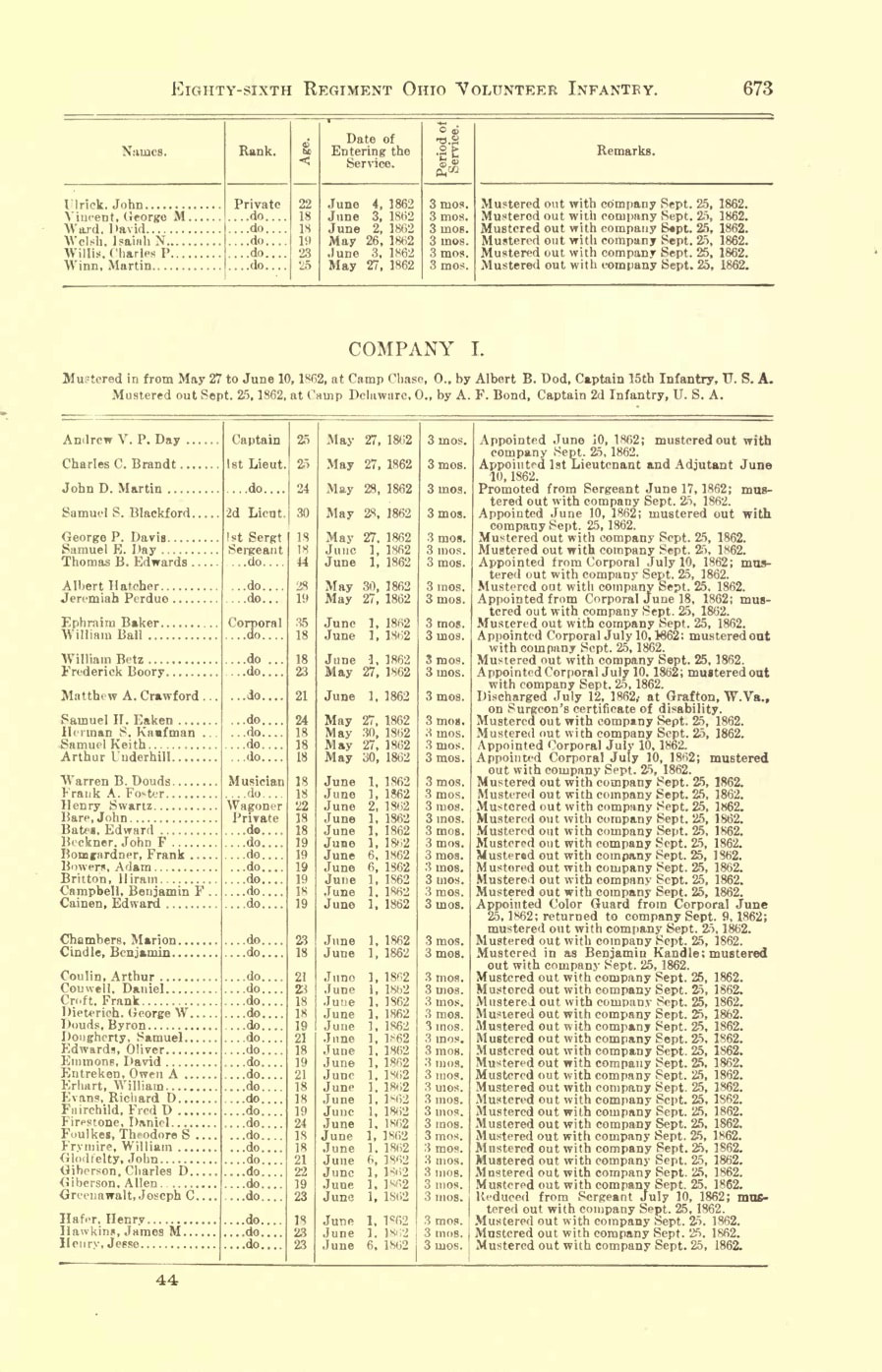

Mr. H. Foster Dear Sir, It is now 10 P.M. and the first leisure moment I have is now devoted in answering your letter. Frank was the last man, or boy, I had expected to see here, but am glad he is here, we need a drummer and he will answer first rate in that capacity, although he is young and tender yet. Capt. Day and my humble self are under obligation to you for the honor and confidence you have confer'd on us by giving your son in our care, be assured that we will do all in our power to keep him as comfortable as possible, we shall care for him the same as if he was a brother or son of ours, he will quarter and eat with us, his baggage will be carried, if gets sick we will attend to him, should it be series we will send him home; To comply with the whole of your request we can not have him musterd into the company for then he could not leave until the three months are up and would have to go wherever the company went, now under the circumstances we propose to let him go with us utill we leave for such places as you will not want him to go, then we will send him home. Our company is now full, we were musterd in with 100 men, the result of the election was for Captain A.V. Day unanimus, for 1st Lieut C.C. Brandt unanimus, for 2nd Lieut. S.S. Blackford from Marlborow by majorety over Marten and Firestone; Sergants to corporal will be appointed by captain and myself to morrow. We expect to get into the 86th regiment for general service and expect to be sent to Cumberland, Md. where the 84th will go tomorrow, will you want Frank to go there and how long over shall stay is uncertain and it is not certain that we shall go eaver there, will not be sent to Washington; Frank can return if we go further then Cumberland. We expect to leave the State next week. if we get into the 86th, the 85 is for State service, our boys are anxius to get out. We have not drawn uniform and equipments yet, expect them to morrow or next day. Our men are in good spirits and good health with the exception of a few cases of diarhea, Frank is quite well, but has to sleep on the soft side of a board to night, government dont furnish feather beds. Frank will draw no pay from the government on account of not being mustered in , but capt. and myself will compensate him so that you and him will be satisfied. The camp is in good order, quarters good and clean, rations ample and good, there are about 4000 three month troops here, no others, also about 1800 prisoners and more of the later are expected sooner. Upon I have nothing further to add, be perfectly easy about Frank, all of your requests shall be complied with, let me hear from you soone and often, I will allways answer prompt. Direct all to Lieut. C.C. Brandt in care of Capt. Day, Camp Chase, Columbus, O. Regards to all....... Yours very respectfully Lieut. Charles C. Brandt Frank A. Foster was our grandmother Helen Foster Pennock Jewitt's uncle; that is to say her mother Florence Foster's brother. Florence and Frank, along with their siblings Charlie and Marion, were the children of Henry A. Foster and Mary Ann Zimmerman. More on all of these relatives in future posts. But for now, let's explore this firsthand account of life as a 14-year-old drummer boy in the Ohio Volunteer Infantry during the summer of 1862. Frank was a member of the 86th Regiment Ohio Volunteer Infantry (OVI). His was the three-month regiment mustered in May 27 - June 10, 1862, and mustered out September 25, 1862. He was in Company I. His name is listed here about a third of the way down... Rank: Musician. The regiment was assembled at Camp Chase in Columbus, Ohio, about 150 miles from Frank's hometown of Minerva, a small farming community. At that time, it would have been about a three- or four-day journey under good travel conditions. At first I was amazed that his parents would have allowed him to travel so far from home at the age of 14 and more importantly... Why would his parents allow him to be subject to the dangers of war? Upon further reading, I discovered that, especially during the earlier and less deadly years of the war, a farm boy getting sent off to join the soldiers for a summer was considered to be a lot like going off to summer camp, and it was a privilege or special treat for a young man to get the opportunity through family friends or other connections, to experience being in a real army. Frank's assignment as drummer boy also meant he would not be exposed to the kind of danger the other soldiers might; in fact drummer boys and buglers were generally entitled to better living conditions than the rest of the troops. Why did all the regiments have musicians? May 22, 2015 feature article by Timothy Walch in the Statesman Journal, an Oregon newspaper: Music was an integral part of the war from recruitment to battle, to bereavement and finally to homecoming. Music woke the troops at dawn and sent them to bed at night. More important, music stirred patriotic spirits, directed troops in battle, buried the dead and celebrated victory. The most elemental form of Civil War music was heard on the field of battle. The sound of fife, drum and bugle gave instructions to the troops to advance or retreat among other actions. Through the smoke and confusion, these sounds provided direction and focus to the action at hand. According to Wikipedia, initially musicians were required in each military unit. Young boys were assigned to be musicians so that the older boys and men would be available to fight. A Union army regulation of July 1861 required every infantry, artillery, or cavalry company to have two musicians and for there to be a twenty-four man band for every regiment. However, the July 1861 requirement was ignored as the war dragged on, and as riflemen were more needed than musicians. And what about Camp Chase: What was it like? Can you still see it today? According to the Ohio History Connection, part of the Ohio History Center based in Columbus, OH: In 1861, the federal government authorized the creation of Camp Chase. Organized in Columbus, it was a recruitment and training center for the Union Army. Camp Chase also served as a prison camp. Civilians loyal to the Confederacy and Southern soldiers were held inside the prison stockade. During 1861 and early 1862, most of the prisoners were from Kentucky and western Virginia and were arrested for their disloyal political sentiments. Following the Battles of Fort Henry and Donelson in February 1862, Union authorities detained numerous Confederate officers and enlisted men as prisoners of war at Camp Chase. During 1863, the number of prisoners housed at Camp Chase at one time was more than eight thousand men. Living conditions at Camp Chase prison camp were harsh. The large number of men in close quarters also led to outbreaks of disease. During the course of the Civil War, over two thousand Confederate prisoners died at Camp Chase, and by 1863, the prison established its own cemetery. The Union military closed Camp Chase at the end of the Civil War. Over the years, the location, now known as Columbus' Hilltop neighborhood, was redeveloped for residential and commercial use. What remains to commemorate the site today is two acres of land, consisting primarily of the Confederate cemetery. In 1896, William Knauss, a former officer in the Northern army, organized a memorial service for the dead Confederates. Judge David F. Pugh, a former enlisted soldier with the 46th Ohio Volunteer Infantry which saw much frontline action during the war, said in his speech at that service: "Carrying two wounds made by Confederate bullets, I am perfectly willing that their graves may be decorated, and even to participate in it when their survivors are not numerous enough to do it. I am willing to admit that their heroism is part of our national heritage." On June 7, 1902, a monument to the Confederate dead was erected at the cemetery. Memorial services have been held at the cemetery every year since 1896. Camp Chase is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. They were men who died for a cause they believed was worth fighting for and they made the ultimate sacrifice. Postscript:

The bronze statue of the confederate soldier atop the cemetery's memorial structure was vandalised in 2017 following a deadly white nationalist rally at Charlottesville, Virgina. With funding from the U.S. Department of Veterans' Affairs, the toppled and decapitated statue was restored and replaced in May of 2019, amidst controversy. Tim Nosal, a spokesman for the Veteran's Affairs National Cemetery Administration in Washington, D.C., said the Camp Chase cemetery on the National Register of Historic Places falls under the National Preservation Act of 1966, which establishes government-wide policies about responsible stewardship for historical properties. Learn more here. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. ArchivesCategories |

Jewitt-Pennock-Foster and Cool-VanPelt Family History Copyright © 2015

RSS Feed

RSS Feed